Note: The creation of this article on testing Link Purpose (Link Only) was human-based, with the assistance of artificial intelligence.

Explanation of the success criteria

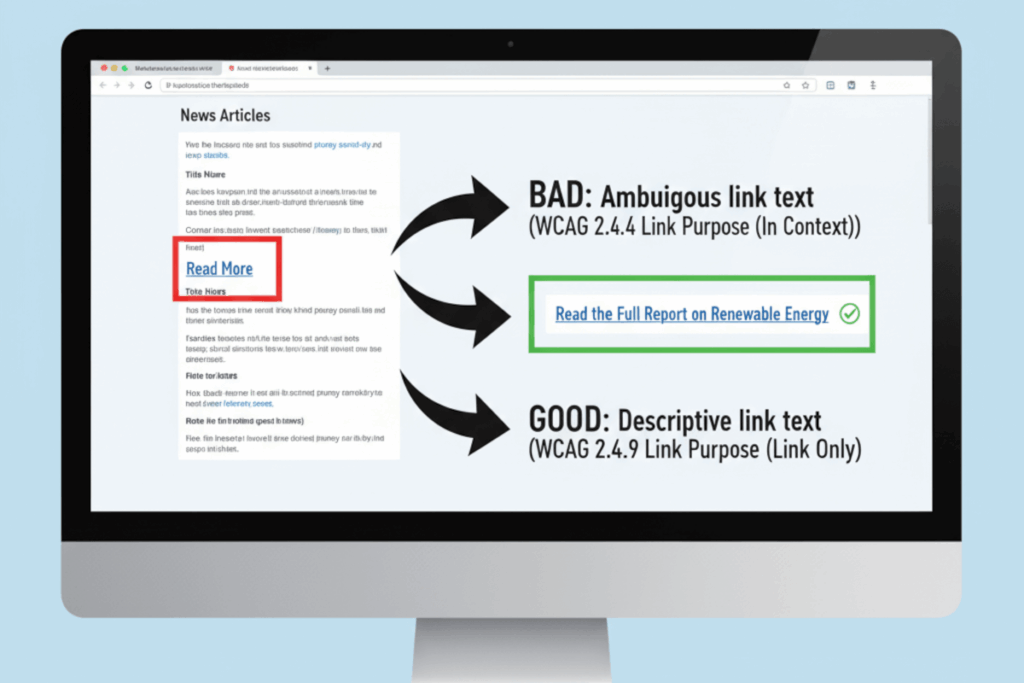

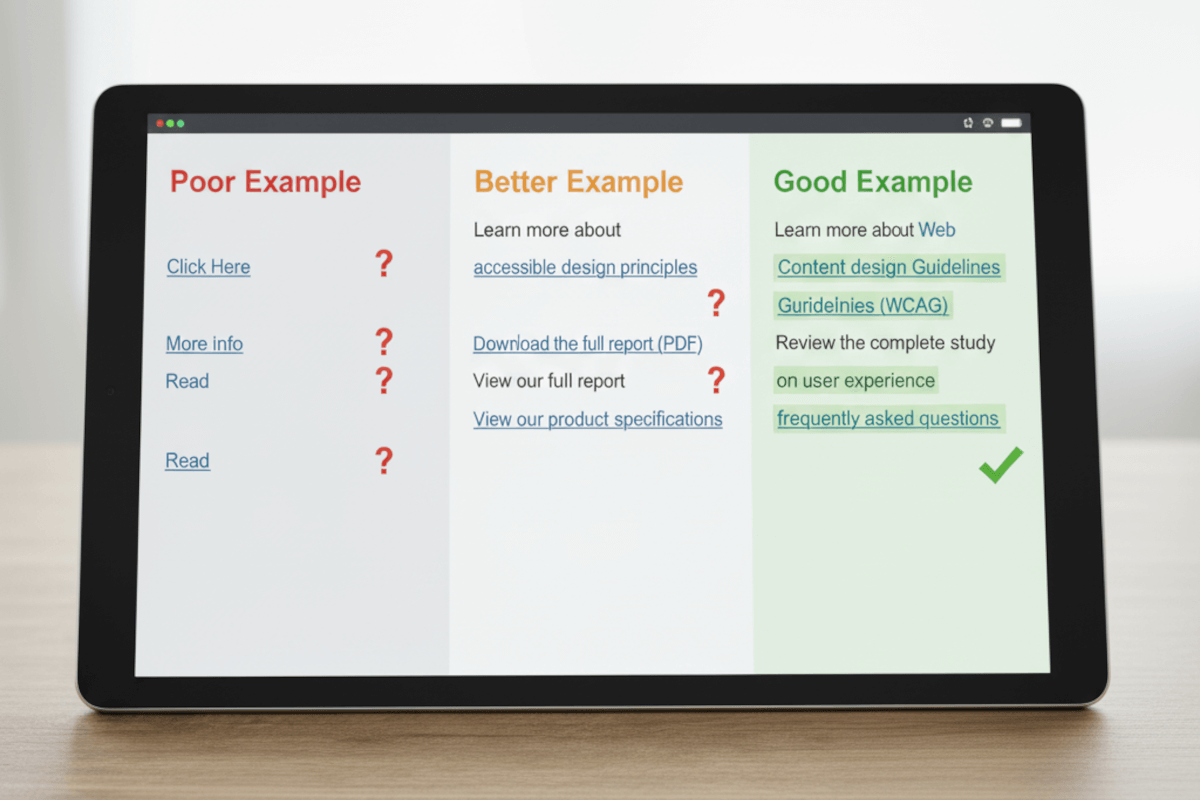

WCAG 2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only) is a Level AAA conformance level Success Criterion. It challenges us to go beyond compliance and design for true understanding. Every link should communicate its purpose through its text alone, without relying on surrounding context or visual cues. When users encounter a link, whether by voice command, keyboard, or screen reader, they should instantly know what it does and where it leads.

“Download annual report (PDF)” is unambiguous. “Click here” or “Read more,” on the other hand, forces users to guess. For someone navigating by audio or with limited visual context, that guesswork creates friction. Meeting this criterion removes that uncertainty, creating experiences that are intuitive, inclusive, and credible.

While Level AAA requirements like this are aspirational, striving for them signals a deeper cultural shift: accessibility as a strategic advantage, not a checkbox. Organizations that prioritize this level of clarity are making a statement, every interaction on their platform is intentional, transparent, and built for everyone.

Who does this benefit?

- Screen reader users gain efficiency, as they often navigate link lists independently of page content. Clear link text means they can decide where to go without context.

- People with cognitive disabilities experience less cognitive load and confusion, since descriptive links provide immediate understanding.

- Users with visual impairments benefit from self-explanatory link text that’s easy to recognize even with magnification or partial visibility.

- Keyboard-only users can navigate with greater speed and accuracy, without needing to explore surrounding layouts for meaning.

- Mobile users enjoy clearer, voice-command-friendly interactions, especially when scanning or navigating hands-free.

When links stand on their own, users don’t have to interpret, they can act. This clarity improves not only accessibility but also the credibility and user trust of your digital experience.

Testing via Automated testing

Automation delivers scale and speed. It efficiently scans for generic link text like “click here” or “learn more,” flagging common issues across vast content sets. It’s an excellent early warning system, but it stops short of understanding intent. Automated tools can’t determine whether “More about sustainability” is meaningful or vague, they simply check syntax, not semantics.

Testing via Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial Intelligence extends that reach. By using natural language processing and contextual understanding, AI can detect whether link text carries meaning on its own. It recognizes patterns in repeated phrasing, identifies ambiguous language, and highlights potential user confusion across templates. Yet, AI still lacks the full nuance of human interpretation, it understands words, but not always purpose or tone.

Testing via Manual Testing

Human testers bring empathy and expertise to the process. They experience the interface as users do, isolating links to see if their intent remains clear when read out of context. They evaluate not just wording, but also visual presentation, grouping, and cognitive effort. Manual testing is slower and more resource-intensive, but it remains the most accurate reflection of real-world usability and understanding.

Which approach is best?

A single testing method can’t capture the full intent of WCAG 2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only), a criterion that asks us to look beyond mechanics and into meaning. To evaluate whether every link truly stands on its own, organizations need a hybrid testing strategy that unites automation, artificial intelligence, and human expertise. Each plays a distinct role in ensuring that users can trust every interaction and navigate without hesitation.

Automated testing forms the foundation of this process. It rapidly scans websites to uncover patterns of weak link text, phrases like “click here,” “read more,” or “learn more” that offer no independent meaning. This first layer provides speed and consistency, flagging systemic issues that might otherwise go unnoticed across large digital ecosystems. Yet, automation has its limits. It can detect the presence of link text, but not whether that text makes sense to a human being navigating in isolation.

That’s where AI-based testing elevates the analysis. Using natural language processing and semantic modeling, AI can evaluate whether a link’s purpose is clearly expressed through its wording alone. It recognizes patterns of ambiguity, identifies recurring context-dependent phrasing, and predicts potential misunderstandings across templates or content types. This introduces intelligence and nuance, but even the most advanced AI can’t fully grasp intent, empathy, or user experience.

The final and most critical layer is manual testing, where human evaluators bring judgment, empathy, and lived experience to the process. Skilled testers isolate links to see if their meaning holds up out of context, assess how assistive technologies interpret them, and consider how visual design reinforces, or undermines, clarity. This step validates not only compliance but the usability and trustworthiness of every link on the page.

When these three approaches work together, they form a comprehensive, intelligent, and human-centered testing framework. Automation delivers efficiency, AI uncovers hidden patterns, and manual testing ensures that what passes technically also works experientially. The result is not just accessible content, it’s digital communication with integrity, where every link is a promise users can understand and trust.

Related Resources

- Understanding Success Criterion 2.4.9 Link Purpose (Link Only)

- Using Link Titles to Help Users Predict Where They Are Going

- mind the WCAG automation gap

- WebAIM Techniques for Hypertext Links

- Providing link text that describes the purpose of a link

- Providing link text that describes the purpose of a link for anchor elements

- Providing text alternatives for the area elements of image maps

- Using CSS to hide a portion of the link text

- Providing links and link text using the Link annotation and the /Link structure element in PDF documents

- Providing replacement text using the /Alt entry for links in PDF documents

- Combining adjacent image and text links for the same resource