A WordPress theme is more than a skin. It is a coordinated system of PHP templates, CSS, and scripts that defines how content is structured, presented, and experienced. Every WordPress site depends on a single active theme to function, which makes the theme a foundational architectural decision, not a cosmetic one.

As of the writing of this article, WordPress.org offers 7,998 themes spanning nearly every imaginable use case, blogs, eCommerce, entertainment, portfolios, and more. Among the available feature filters is one labeled “Accessibility-Ready.” If your goal is to create an accessible WordPress website, this is where you should begin. Not because it guarantees accessibility, it does not, but because it establishes a baseline that respects core accessibility expectations rather than fighting against them.

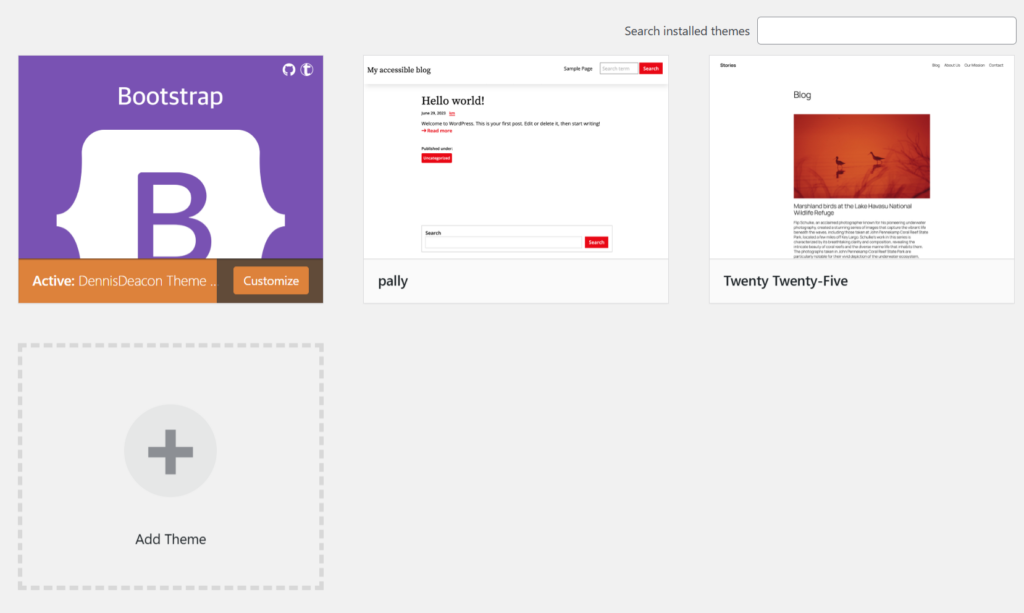

I have used Accessibility-Ready themes from WordPress.org many times. The theme powering this site today, pally, is one of them. I moved to pally after uncovering a serious accessibility issue in a previous theme, an issue that quite literally made someone physically ill. Since then, pally has served me well. That said, no theme is ever a perfect fit. There are several design and implementation details that no longer align with how I want this site to evolve, which makes 2026 the right moment for a visual and structural reset.

I could take the conventional route and create a child theme that extends pally, layering my changes on top. That approach is valid and often recommended. It just is not how I am wired. I prefer understanding and controlling the full stack rather than negotiating with inherited decisions. So instead of modifying a parent theme, I am starting closer to first principles, using a framework I know deeply, Bootstrap.

Bootstrap as an accessible starting point

Bootstrap is a deliberate choice. I know the class system, the layout patterns, and how to bend it to my will without fighting the framework. That familiarity dramatically reduces development time. Through an accessibility lens, Bootstrap is a strong starting point for building accessible themes, though it is not flawless. It makes many good decisions by default, and it still requires scrutiny, testing, and occasional correction. Those gaps are exactly the kinds of issues we will surface and address during development.

The WordPress.org theme repository currently lists 744 Bootstrap-based themes, including several starter themes designed specifically for customization. If you choose this path, ensure the theme is built on the current Bootstrap 5.x release. Older versions introduce both accessibility and security risks that you do not want to inherit.

In my case, I am not starting from an existing theme. I am building from scratch. Technically, that could mean manually pulling in Bootstrap’s CSS and JavaScript files and writing every PHP template myself. Practically, efficiency matters. To accelerate the setup without compromising control, I am using a Bootstrap Starter Theme generator for WordPress.

The process is straightforward. You provide a theme name, a slug, which is the programmatic identifier in lowercase starting with a letter, author details, a URL, and a description. Accept the terms, download the generated ZIP file, upload it to your WordPress instance, and activate the theme. From there, you have a clean, Bootstrap-powered foundation that you fully own, ready to be shaped with accessibility intentionally designed in, not retrofitted later.

This is the work. Accessibility does not begin with overlays or audits. It begins with the decisions we make at the theme level, long before the first line of content is published.