Note: The creation of this article on testing Dragging Movements was human-based, with the assistance of artificial intelligence.

Explanation of the success criteria

WCAG 2.5.7 Dragging Movements is a Level AA conformance level Success Criterion. It is all about ensuring that interaction is never a barrier. It requires that any functionality relying on a dragging gesture, such as click-and-drag, press-and-hold, or swipe-to-move, can also be operated with a single-pointer action like a simple click or tap. This criterion recognizes that complex gestures can be exclusionary. What seems effortless to one user, dragging a slider, sorting a list, or repositioning an object, may be impossible for someone with limited dexterity, tremors, or motor impairments.

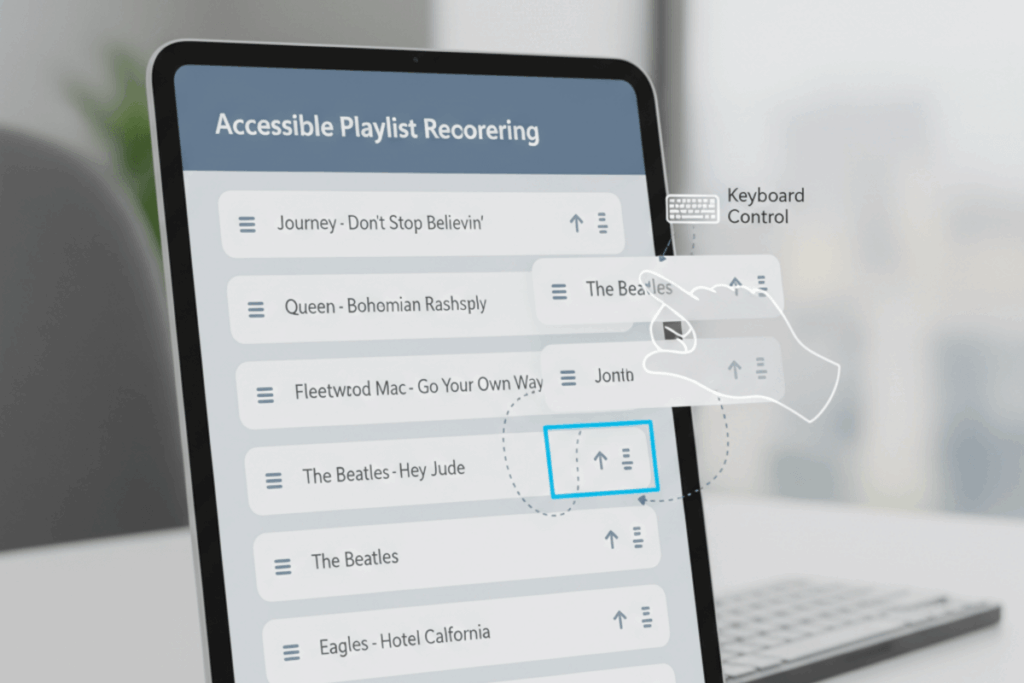

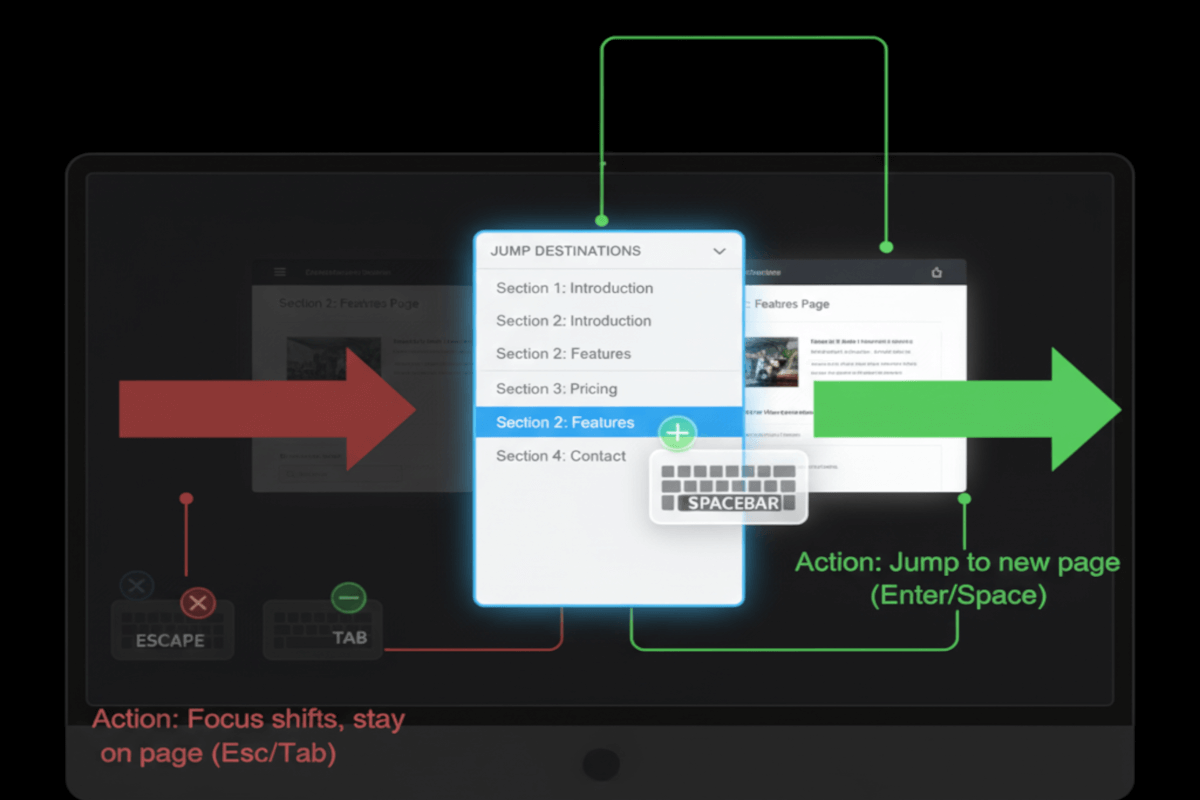

Designing inclusively here means offering straightforward alternatives: buttons to move objects instead of dragging them, keyboard commands to reorder items, or tap-based controls for map navigation. These alternatives not only meet accessibility standards but also enhance usability for everyone, including users with temporary impairments, those using voice or switch inputs, and even people on mobile devices in less-than-ideal conditions. Accessibility, at its best, is universal usability.

Who does this benefit?

- Individuals with limited motor control or dexterity challenges, such as those with tremors, cerebral palsy, or muscle weakness.

- People using assistive input tools, mouth sticks, head pointers, or switch devices, that can’t easily perform dragging motions.

- Users of speech recognition software who rely on verbal commands rather than physical gestures.

- Anyone with temporary limitations, an injured hand, reduced mobility, or operating a device in motion.

- Users on touchscreens where precision is compromised by small targets or inconsistent touch sensitivity.

When dragging movements are supplemented with single-pointer or keyboard alternatives, interactions like sliders, drag-and-drop components, and map panning become accessible to all. It’s a simple but profound shift, from exclusion through complexity to inclusion through flexibility.

Testing via Automated testing

Automated testing provides the speed and scalability essential for modern accessibility programs. Tools can scan large codebases to identify known drag-and-drop patterns, HTML5 dragstart or dragend events, or third-party libraries like React DnD and jQuery UI, and flag them for review. This automation helps development teams spot potential accessibility gaps early in the design process and reduces manual workload.

However, automated testing has a clear ceiling. It cannot simulate the human act of dragging or assess whether the provided single-pointer alternative truly replicates the functionality. It sees patterns, not experiences. As such, automation is a strong first pass, ideal for discovery and triage, but insufficient for validation.

Testing via Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial Intelligence elevates accessibility testing beyond simple code analysis. Through pattern recognition and behavioral inference, AI-based tools can identify complex gestures, predict user interaction challenges, and even simulate alternative input scenarios. Machine learning can detect unconventional implementations where traditional automated tools fall short, while generative AI can analyze interface logic to anticipate where accessible alternatives may be missing.

Yet, AI’s insight comes with caveats. It still lacks the nuanced context of human experience. It cannot determine whether an alternative action feels intuitive, whether it maintains task equivalence, or whether it accommodates users with real-world mobility limitations. AI is immensely valuable for prioritization and insight, but it remains an assistant, not an arbiter.

Testing via Manual Testing

Manual testing is the linchpin of verifying compliance with WCAG 2.5.7. It bridges the gap between theoretical accessibility and lived experience. Human testers can engage directly with interfaces using multiple input methods, mouse, keyboard, touch, stylus, voice, or assistive technology, to determine whether dragging is truly optional.

This method captures subtle but critical factors: timing sensitivity, input precision, discoverability of alternatives, and overall usability. Manual testing exposes whether the design genuinely works for all users, not just whether it technically meets the standard. While it requires time, cost, and expertise, it delivers the most trustworthy and actionable insights.

Which approach is best?

Relying on a single testing method is never sufficient to ensure full WCAG 2.5.7 Dragging Movements compliance. A hybrid approach to testing WCAG 2.5.7 Dragging Movements leverages the strengths of automated, AI-based, and manual testing to achieve comprehensive, efficient, and accurate results.

The process begins with automated testing, which can rapidly scan for elements and scripts associated with drag-and-drop functionality, such as use of HTML5 dragstart, dragend, or JavaScript libraries like React DnD or jQuery UI. Automated tools can flag these instances as potential accessibility concerns and identify where keyboard or pointer event handlers might be missing. While this step cannot determine whether an accessible single-pointer alternative exists, it efficiently narrows the testing scope to likely problem areas, saving significant time in large-scale audits.

Next, AI-based testing adds an intelligent layer of contextual understanding. By analyzing UI patterns, behavior flows, and interaction models, AI can infer which elements rely on dragging and predict whether an equivalent, non-dragging alternative might be intended or missing. Advanced AI tools can also simulate user interactions across multiple input methods, such as touch gestures versus mouse clicks, and assess whether each produces consistent outcomes. Additionally, AI models trained on accessibility patterns can prioritize the most critical instances where user impact is likely highest, helping testers focus manual efforts more strategically. While AI cannot conclusively determine compliance, it bridges the gap between raw code analysis and human judgment.

The final and most crucial phase is manual testing, where expert testers validate functionality through real-world interactions. This involves attempting to perform dragging actions using single-pointer methods, such as a single click, tap, or key press, to confirm that equivalent outcomes are possible. Manual testers also verify that these alternatives are intuitive, discoverable, and operable for users with limited dexterity or who rely on assistive technologies like switch devices or voice input. Usability testing at this stage provides critical confirmation that technical compliance translates into genuine accessibility.

WCAG 2.5.7 isn’t merely about replacing dragging gestures with clicks. It’s about recognizing that true accessibility stems from choice, offering users multiple ways to achieve the same goal. Testing strategies that reflect this principle ensure more than conformance; they build digital experiences that are inherently inclusive, resilient, and user-centered.

When we design and test with accessibility in mind, we don’t just meet standards, we create digital environments that welcome everyone, regardless of ability, context, or device.