Note: The creation of this article on testing Labels or Instructions was human-based, with the assistance on artificial intelligence.

Explanation of the success criteria

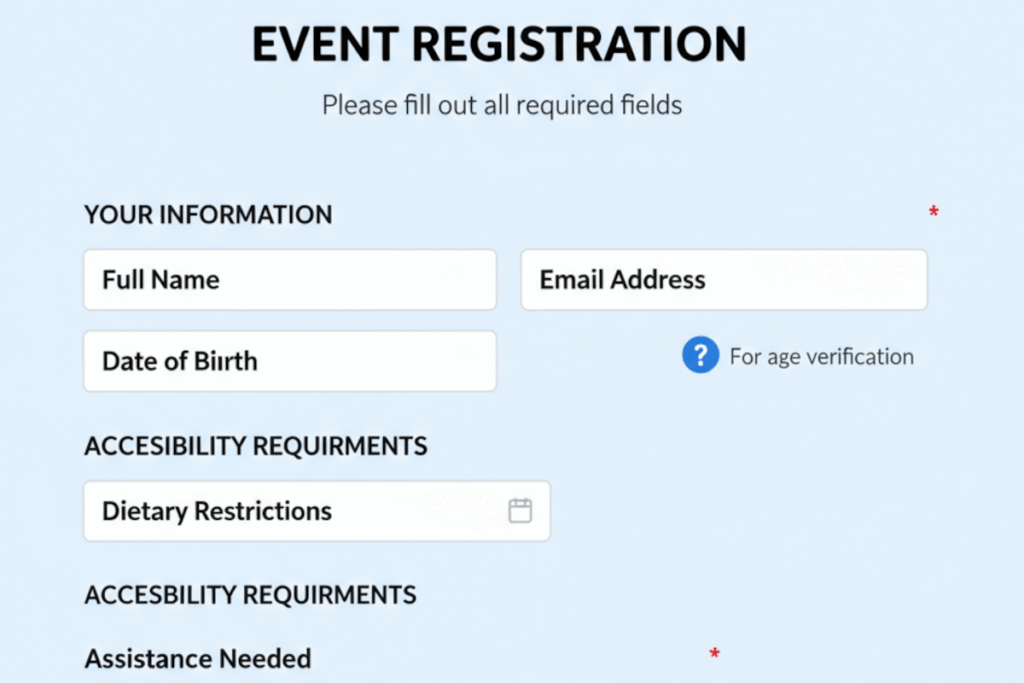

WCAG 3.3.2 Labels or Instructions is a Level A conformance level Success Criterion. It ensures that users understand what is expected when interacting with input fields and controls. It requires that all form elements and interactive components include clear, descriptive labels or guidance that communicate their purpose and how to use them. This clarity reduces user errors, improves task completion rates, and enhances confidence for people with cognitive, learning, or visual disabilities.

Effective labeling goes beyond simple field names, it anticipates user needs, provides context, and aligns with design and content best practices. In digital accessibility, this criterion is foundational: it bridges usability and inclusion by transforming digital interactions from guesswork into intuitive experiences. Thoughtful implementation not only supports accessibility compliance but elevates overall UX quality, reinforcing that accessibility is an integral part of intelligent design, not an afterthought.

Who does this benefit?

- People with cognitive or learning disabilities benefit through clear guidance that reduces confusion, helping them understand what’s required before interacting with a form or control.

- Users with visual impairments gain clarity when screen readers accurately announce descriptive labels that communicate purpose and context.

- People with memory or attention limitations rely on visible, consistent instructions to stay focused and complete tasks without unnecessary frustration.

- Non-native language speakers find explicit labels and examples invaluable for comprehension, minimizing errors caused by ambiguous wording.

- Older adults benefit from straightforward, intuitive labeling that reduces cognitive load and enhances digital confidence.

- All users experience smoother interactions, faster task completion, and fewer mistakes, demonstrating that accessibility-driven design is simply good design for everyone.

Testing via Automated testing

Automated testing offers speed and scale, efficiently identifying missing labels, improper associations, or non-unique id values across large codebases. These tools excel at structural validation, ensuring programmatic relationships are correctly implemented. However, automation alone falls short in evaluating clarity, context, or relevance. It cannot determine if a label is descriptive enough to help users understand an input’s purpose or if instructions are intuitive within the flow of a task.

Testing via Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI-based testing elevates this process by applying natural language processing and pattern recognition to assess label quality and intent. AI can analyze semantic meaning, detect vague or repetitive wording, and even predict potential user confusion. This contextual intelligence bridges gaps left by automation, offering insight into the usability and cognitive accessibility of instructions. Yet, AI still operates within learned models, it may misinterpret context-specific terminology or design patterns that are unconventional but valid, requiring careful oversight to avoid false positives or missed issues.

Testing via Manual testing

Manual testing remains the gold standard for verifying real-world accessibility. Human testers bring empathy, experience, and situational awareness, recognizing whether instructions appear when users need them, whether visual cues align with assistive technology output, and whether the guidance genuinely supports comprehension. The downside is scalability: manual testing is time-intensive and requires expertise to interpret nuanced language and design intent.

Which approach is best?

A hybrid approach to testing WCAG 3.3.2 Labels or Instructions delivers the most comprehensive and reliable results by leveraging the strengths of automation, AI, and human expertise in a complementary workflow.

The process begins with automated testing, which efficiently scans the entire digital experience to detect missing or improperly associated labels, invalid aria-labelledby relationships, or incomplete form markup. These machine-precise checks create a foundational map of structural issues that could block users from understanding or interacting with inputs.

Next, AI-based testing takes the analysis further, applying natural language processing and machine learning to evaluate the clarity and intent of labels and instructions. AI can flag ambiguous or redundant phrasing, predict user confusion based on cognitive load, and identify patterns that deviate from accessibility and UX best practices. This layer adds semantic intelligence, something traditional automation can’t achieve.

Finally, manual testing validates the user experience in real-world scenarios. Human testers assess whether labels appear at the right time, if instructions are perceivable across modalities (visual, auditory, tactile), and whether the guidance genuinely helps users complete their tasks. They evaluate tone, context, and clarity, areas that machines can approximate but not fully understand.

Together, this hybrid model forms a continuous loop of efficiency and empathy: automation handles scale, AI refines meaning, and human insight ensures usability. This approach transforms testing from a checklist exercise into a dynamic, user-centered strategy, one that not only meets WCAG 3.3.2 compliance but also advances the overall accessibility maturity of a digital product.

Related Resources

- Understanding Success Criterion 3.3.2 Labels or Instructions

- mind the WCAG automation gap

- More Than Just Text: The Real Power of Labels

- Accessible Names and Labels: Understanding What Works and What Doesn’t

- Writing Accessible Form Messages

- Providing descriptive labels

- Using the aria-describedby property to provide a descriptive label for user interface controls

- Using aria-labelledby to concatenate a label from several text nodes

- Using grouping roles to identify related form controls

- Providing expected data format and example

- Providing text instructions at the beginning of a form or set of fields that describes the necessary input

- Positioning labels to maximize predictability of relationships

- Providing text descriptions to identify required fields that were not completed

- Indicating required form controls using label or legend

- Indicating required form controls in PDF forms

- Using label elements to associate text labels with form controls

- Providing labels for interactive form controls in PDF documents

- Providing a description for groups of form controls using fieldset and legend elements

- Using an adjacent button to label the purpose of a field

- Describing what will happen before a change to a form control that causes a change of context to occur is made